Founded in 2009, Huddersfield Contemporary Records (HCR) continues to go from strength to strength. Not only as a showcase for what is surely now the powerhouse for new music in UK academe, but as a record label in its own right.

Ending today (30 September), NMC is offering 20% off all HCR releases. Get yours now.

To help you on your way, here are reviews of the three most recent releases.

Diego Castro Magas: Shrouded Mirrors (HCR10 CD)

The Chilean guitarist Diego Castro Magas is a PhD candidate in performance at Huddersfield. A former student of Oscar Ohlsen, Ricardo Gallén and Fernando Rodríguez, he has in the last decade or so become a specialist in contemporary repertoire (his first release, in 2009, featured the first recording of Ferneyhough’s guitar duet no time (at all), with his Chilean colleague José Antonio Escobar).

A performer clearly keen to push his instrument’s repertory to its limit (witness his remarkable realisation of a kind of nostalgia, written for him by the composer Michael Baldwin), on Shrouded Mirrors he takes on more conventional challenges – in whatever sense music by James Dillon, Brian Ferneyhough, Michael Finnissy and some of their younger admirers, Bryn Harrison, Wieland Hoban and Matthew Sergeant, might be considered ‘conventional’.

Hoban’s Knokler I (2009) takes perhaps the most radical approach, using a multi-stave tablature notation and a very low scordatura to distort the sound and physical familiarity of the guitar as much as possible. Based on a poem by the Norwegian poet Tor Ulven, it emphasises the physicality of the guitar (knokler meaning bones in Norwegian), as well as the poem’s collage of images. But whereas many composers working in this fashion (including some of those on this CD) produce music of sharp prickles and vertiginous drops, Hoban writes a queasy, unpredictable melting that is distinctive and strangely attractive.

Sergeant’s bet maryam (2011) is a characteristic blend of the headlong and the eldritch, and (like other works by Sergeant) takes its title from an Ethiopian church – this one a small, rock-hewn building on the Labilela World Heritage site. A feature of the church is a pillar that is reputedly inscribed with the Ten Commandments, the story of the excavation of Labilela, and the story of the beginning and end of the world. Deemed too dangerous for mortal eyes, however, the pillar has been veiled since the 16th century, which Sargeant’s piece expresses through the use of a melodic cycle within the piece that is variously exposed or veiled.

Also notable is Bryn Harrison’s M.C.E. (2010), which is quite the loveliest Harrison piece I have heard in some time. Perhaps a source of its particular expressive clarity is that it is named after M.C. Escher, an artist whose work shares much with Harrison’s own.

Of the pieces by the three ‘senior’ composers, Ferneyhough’s Kurze Schatten II has been recorded several times. I know two versions by Geoffrey Morris, released in 1998 (on Etcetera with ELISION) and by the Australian Broadcasting Company in 2000. Castro Magas’s version is the slowest of all three (a relative term), and as a result contains more space; but it also features sharper angles between the music’s intersecting planes (most clearly heard in the third movement’s tapestry of knocks and stabs). The result is more fragmentary, an emphasis found more explicitly in Ferneyhough’s later music, and a thrilling take on a familiar work. Finnissy’s Nasiye (1982, rev. 2002) dates from the period when the composer was writing many solo works based on folk musics from around the world. Nasiye is based on a Kurdish folkdance, which gradually emerges, movingly and with great dignity, from the deeply personalised context Finnissy has given it. The album’s title piece was composed in 1987 by James Dillon, and is a proper slice of old-school complexity, given eloquent justification by Castro Magas’s playing.

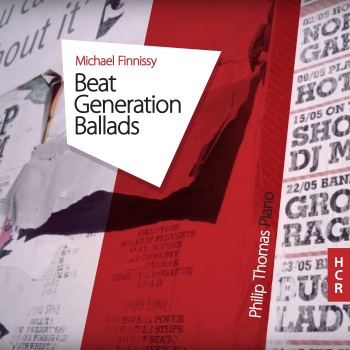

Philip Thomas: Beat Generation Ballads (HCR11 CD)

At Huddersfield, Castro Magas’s supervisor is Philip Thomas – a pianist currently on a remarkably prolific recording streak. His own release for HCR concentrates on two major works by Michael Finnissy: First Political Agenda (1989–2006), and Beat Generation Ballads (2014), the latter of which Thomas premiered at the Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival in 2014.

Like its predecessor, and topical relation, English Country-Tunes, First Political Agenda begins with thunderous sweeps across the keyboard. What grows out of their dying echoes, however, is somewhat different: not the ironically distorted pastoralism (those never-quite restful open spaces) of English Country-Tunes, but a darker, rougher manipulation of raw materials. Its second movement draws on the Benedictus from Beethoven’s Missa solemnis, while the third – ‘You know what kind of sense Mrs. Thatcher made’ – performs a Chris Newman-esque détournement on Hubert Parry’s theme for William Blake’s ‘Jerusalem’, flipping the ultimate musical signifier of England on its end, flattening it and rendering it distressingly mute: a ghastly, heart-stoppingly empty reflection on the ‘sense’ of Britain’s most divisive Prime Minister.

Beat Generation Ballads contains further references to Beethoven (and, in its 30-minute final movement, Finnissy’s first extended use of a variation form), as well as Allen Ginsberg, Irish Republican protest songs, Bill Evans, the bassist Scott LeFaro, and the poet Harry Gilonis. In its short first movement, ‘Lost But Not Lost’, it also features music written when the composer was only 16, a typical gesture of Finnissian self-archaeology.

There’s far too much to consider here in what is supposed to be a short review, but works are major statements, not (I think?) previously recorded, and are done justice by Thomas’s intelligent and critically reflective performance.

Heather Roche: Ptelea (HCR09 CD)

This is the oldest of these three releases; that is, it is the one that has been sitting on my desk the longest. Another Thomas student (she completed her PhD at Huddersfield in 2012), the Canadian-born clarinettist Heather Roche needs little introduction among followers of new music in the UK or Germany, where she now lives. One of the most energetic younger players on the scene, she is a founder member of hand werk, has hosted her own competition for young composers, and writes a widely-read (and actually useful!) new music blog.

Ptelea features works by six composers with whom Roche has formed important artistic relationships: Aaron Einbond, Chikako Morishita, Martin Iddon, Martin Rane Bauck, Pedro Alvarez and Max Murray. As first recital discs go, it’s an unusual one: several of the works are hushed affairs, for deep, close listening. No overt virtuosity here – Morishita’s Lizard (shadow) the closest thing to a ‘typical’ recital piece, albeit a contemporary one – although there is clearly much going on just out of earshot.

The repeated, breathy multiphonics of Bauck’s kopenhagener stille (2013), for example, will appeal to fans of Wandelweiser; Murray’s Ad Marginem des Versuchs (2015) to admirers of Lucier and Sachiko M. Einbond’s Resistance (2012) opens the disc with barely more than the noise of air passing through the bass clarinet’s deep tube, and even this is only gradually augmented with the sounds of keys and, eventually, tones. Yet the work is also infused with the sounds of political protest – marches recorded in New York in 2011–12. Played through a speaker in the clarinet’s bell, these slowly emerge in their own right, a weird progeny of the instrument itself.

Iddon’s Ptelea is yet another a quiet affair. Using Josquin’s Nymphes des bois as a framework, Iddon constructs a slippery polyphony out of an impossible monody – a single instrumental line grouped in such a way that not everything can played at once. Difficult to describe in brief (here’s Iddon’s score), but like much of Iddon’s music a surprisingly simple idea brought to its full fruition.

For me, Iddon’s piece is the stand-out track (I really must get round to writing up his CD on another timbre from a couple of years ago), although Pedro Alvarez’s Instead (2013) comes close for creating something distinctly different from a typical solo clarinet work – odd blocks that nod towards minimalism and Zorn, if anything, although that isn’t giving much away. A strange disc, then, with some strange composers – but all the better for it.