Morgen und Abend, Georg Friedrich Haas’s seventh opera, has just finished its premiere run at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden. I went on the middle Saturday (21 November), and found I had quite a few things I wanted to say about it. I also wrote the introduction to Haas and his music for the programme book, so you can read the following according to how you think that might affect my partiality. To help me write that essay, I did have access to the libretto, as well as some in-house production notes. However, I didn’t hear a note of music in advance.

Morgen und Abend is based on Jon Fosse’s novel of the same name, with a libretto by Fosse himself. Its central character Johannes (Christoph Pohl) is a North Sea fisherman, the son of Olai (Klaus Maria Brandauer) and Signe (not seen). He has a daughter, also Signe (Sarah Wegener), and a wife, Erna (Helena Rasker). However, we encounter Johannes only at the beginning and end of his life: the moments of his birth and of his death, drawn out and placed under the microscope to emphasise their status as transitions, rather than singular points. Very little else happens dramatically.

Beckett-like, you might say. And Fosse’s libretto is full of the sorts of internal rhythms and repetitions that energise Beckett’s own writing:

Why is it so quiet

in there in the room

so strangely quiet

what can it mean

not a sound

and it’s my dear Signe

and the midwife

in there

what can it mean

what’s happening

When a child is born

it doesn’t go so quietly

I know that much

even as a man

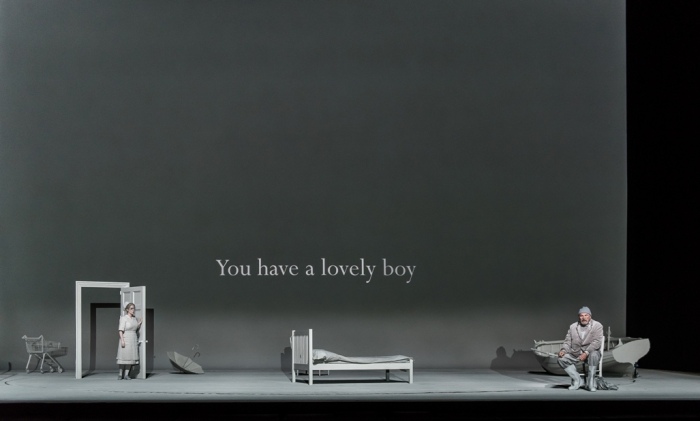

But the work is also unlike Beckett; it is softer, flatter, unflecked with the Irishman’s dark jokes. The tragicomic absurdism of postwar Europe is replaced with a post-digital, 21st-century monochrome. This is reflected not least in the set and costumes, which are all of the same pale blue-grey. As always with Haas everything is in flux: chords continually evolve and devolve, form and collapse, the inevitability of decay providing the music’s essential drive and tempo. In many ways this is (or could have been) a perfect marriage of story and music: we see Johannes through the two fundamental transitions that define a person’s life.

And in the second two-thirds of the opera, which deal with Johannes’ departure from life, this does work well. Fosse’s writing is at times breathtaking – ‘But even if it’s cold,’ dying Johannes says as he takes the hand of Erna’s ghost, who has come to guide him into the afterlife, ‘at least it’s there.’ – and Haas’s music often rises to the occasion. Moments with a flash of tubuular bells and a shimmer of keyed percussion stick particularly in the mind. And while the narrative is stripped back to its absolute bare bones, there are some gentle touches – such as Johannes and his friend Peter (Will Hartmann) reminiscing about cutting each others’ hair – that really lift it. In fact I think the text could have taken one or two more of these – something about Johannes’ daughter Signe, for example, perhaps even a memory of her birth to keep the loops going round.

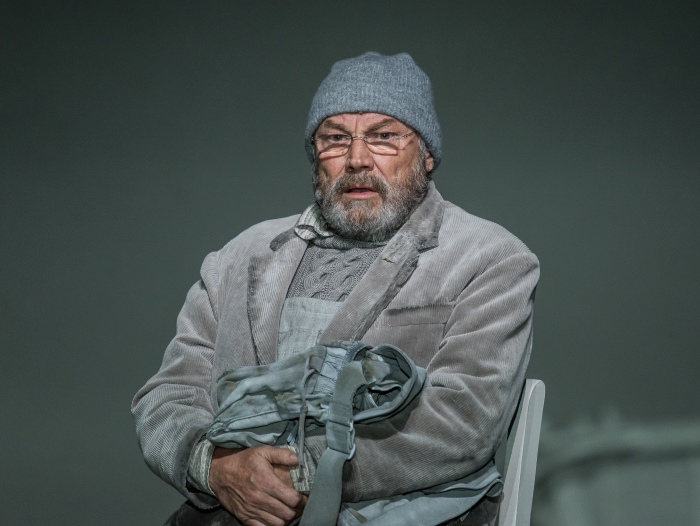

The first third of the opera is much simpler: Johannes’ father Olai waits outside the bedroom, listening to his his wife is in labour. Until the end of this 30-minute scene, when the midwife announces Johannes’ birth, there are no entrances or exits. Even the one long entrance the scene is ostensibly about happens behind a closed door. Olai is nervous, and speaks his lines – in English, so without surtitles. This is important because his accent is thick, and some of his words get lost, especially those which are directed upstage, towards where the bedroom door is. One of these was the first statement of ‘midwife’, a rather important clue as to what was going on.

Haas chooses to set Olai’s monologue to some of his simplest music yet, long-held triads, sometimes blurred with glissandi or otherwise just moving through different orchestrations. Verticals are provided by short bursts of bass drumming by the two percussionists either side of the stage, presumably suggesting something like waves of contractions, but they were not nearly shaped clearly enough to carry much programmatic weight.

Worse, however, is Haas’s decision to have each of Olai’s lines delivered in isolation, with pauses of various lengths in between. This had the effect of stretching a few pages of libretto into half an hour while preserving the structure of Fosse’s text, and maintaining Olai’s monologuing presence. But it also emptied the words entirely of Fosse’s careful and purposeful rhythms. What bounced in writing dragged in sound.

On top of all this was the decision by Graham Vick to have Olai sit for the full 30 minutes. Not stand or move about, not pace up and down. Just sit and speak. He barely moves his arms, even – ironically it is only with the line “if only something would happen” that he shows signs of real agitation.

So music, delivery, text setting, staging and direction are all downplaying it. Individually, none of these is a problem. All together is deathly, and tested even my Wandelweiser-tuned patience. Looking for something, I found myself transfixed by the contrast of the pinkness of Brandauer’s face against the otherwise uniform blue-grey.

Things improve enormously, however, when the midwife (also Wegener) enters. An entrance. And she sings! Suddenly the whole piece lifted off the ground. I’m not always convinced by opera as an artform, particularly a contemporary one, but in this moment it was just what was needed.

Morgen und Abend will be broadcast on Radio 3 on 5 December at 6.30pm.